Justices on the Supreme Court Have No Constitutional Authority Nor Any Moral Basis to Decide What Our Cultural and Moral Norms Shall Be

The vast majority of the Court’s work focuses on issues of little national consequence. This work looks at such things as statutory construction or clarifying the proper application of a long existing rule of law to a rather pedestrian matter that is of importance only to the parties. However, the Court must, on occasion, interpret the Constitution and apply that interpretation to a large overarching constitutional question that carries significant, lasting, and transformative impact on society. Chief Justice Marshall famously wrote that it was “emphatically the province and duty of the Court to say what the law is.” I think that Marshall’s words are meant to apply to these occasions. I also think, he meant to establish for the new nation, a general frame of reference that contains the essential rules, methods, and philosophy of America’s jurisprudence. A careful reading of the quote, along with the fuller explanation that follows in Marbury and other cases, reveals Marshall’s understanding of the Constitution. I do not take him to be claiming a judicial supremacy that resides in the will of the justices. Quite to the contrary, his quote and words that follow in Marbury and elsewhere, instruct us that supremacy lies in the language of the Constitution. It is the duty of the Court to base its decisions on what the language of the document actually conveyed when written. Marshall pledges allegiance to the Constitution, not judicial will.

To come to this conclusion, I focus first on the words “duty of the Court” and take them to mean that duty implies that the Court is bound to something larger than itself, something more profound, and something more lasting than the internal will of the justices; and that larger ‘something’ is the written words of the Constitution. In Cohens v Virginia, Chief Justice Marshall says, “A constitution is framed for ages to come, and is designed to approach immortality as nearly as human institutions can approach it.” In Osborne v Bank of the United States he says, “ Judicial power, as contradistinguished from the power of laws, has no existence, Courts are the mere instruments of the law.” From these statements, I conclude that Mr. Marshall means that neither the will of the Court nor its interpretations are the supreme law; the supreme law stands separate and alone as its own being. In the United States that ‘being’ is the words, clauses, articles, and whole document of the Constitution.

The Marbury quote also states that “it is the province of the Court to say what the law is” but he does not say that such province lies solely and only with the Court. I believe that this wording, in Marshall’s view, keeps him within the founding principles of the separation of powers. The fact that the thirty-five years long Marshall Court and the twenty-eight years long Taney Court rarely intervened into national affairs to overtly reverse or overturn a Congressional act supports this conclusion.[1]

I have often asked myself, “Why was the Court reluctant, over these many years, to intervene into what Congress did? “ For me the answer lies in large part in these words of Marshall’s, “Judicial power, as contradistinguished from the power of laws, has no existence, Courts are the mere instruments of the law”. It is apparent, at least to me, that he places the supreme law not in the interpretations of the Court but in the physical being of Constitution. This is why senior judges trained in the law, history, and legal philosophy who have spent large portions of their lives working in the courts reading and applying law are uniquely qualified to find and extract constitutional meaning from the words, clauses, articles, and whole document of the Constitution.

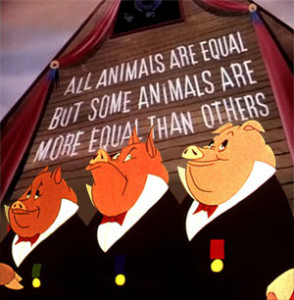

If, as I have done, I pledge my allegiance to the words and language of the Constitution, I must, if I am to be thorough, comment on the long line of precedent that stands separate from the Constitution. Do I believe that precedent cases stand as supreme law of the land? My answer is that they do not. There is only one supreme law of the land and that is the Constitution. Precedent cases exist as Court manifestations of the outcome the Court, in the exercise of its constitutional duty and oath, has determined the supreme law, in a particular instance, seems to require. If that manifested outcome is reflected and contained in the words, clauses, articles, or whole body of the Constitution, it stands as legitimate law. However, that particular precedent case, valid law though it is, remains subordinated to and a creature of the Constitution. Justice Antonin Scalia is one of my several sources for this line of jurisprudential reasoning. Critiquing the current modern mode of judicial review he says, “The starting point of the analysis will be Supreme Court cases, and the new issue will presumptively be decided according to the logic that those cases expressed, with no regard for how far that logic, thus extended, has distanced itself from the original text and understanding.”[2] He goes on to say “Worse still, however, it is known and understood that if that logic fails to produce what in the view of the current Supreme Court is the desirable result for the case at hand, then like good common law judges, the Court will distinguish between its precedents, or narrow them, or if all else fails overrule them, in order that the Constitution might mean what it ought to mean.”[3] This is followed by “Never mind the text that we are supposedly construing; we will smuggle these new rights in, if all else fails, under the Due Process Clause.”[4] Justice Scalia’s withering description of judge-willed interpretation articulates more eloquently than I could, how the will of the judge has replaced the will of the Constitution.

I do not want to leave the impression that I believe precedent valueless. Carefully and faithfully extracted from very similar cases, precedent rules give law its necessary continuity. I take exception with what I call improper and disingenuous application of precedent. Robert Rantoul, an early American politician and practicing lawyer said it well. In a Fourth of July speech many years ago, he asserted, “The judge makes law, by extorting from precedents something they do not contain. He extends his precedents, which were themselves extensions of others, till, by this accommodating principle, a whole system of law is built up without authority or interference of the legislator.” Justice Scalia comments on Mr. Rantoul’s remarks saying, “Substitute the word people for legislature and it is a perfect description of what the modern American courts have done with the Constitution.” There is valid precedent which is faithful to the law, and there is conjured precedent used to force upon society the will of the judge. I endorse the former and eschew the later.

Mr. Scalia also describes another phenomenon of the modern Court. That is that the modern Court’s Constitution seems to be comprised only of he Bill of Rights and the due process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. The seven original articles that are the structural framework for our federalist system of government have somehow faded off the pages as if they had been written in disappearing ink. In fact, the Court has constructed a fast moving assembly line that creates categories of rights as fast as postmodern progressive lawyers can invent them. These so called rights are then packaged as products to sell in the political market place. This practice is not constitutional and it is a danger to social stability.

I want to make one last reference to Justice Scalia as it will bring into finer focus my jurisprudential approach in interpreting the words of the Constitution and views on judicial supremacy. Mr. Scalia differentiates between strict construction and reasonable construction.[5] I, following the teaching of my jurisprudential betters Justice Marshall and Justice Scalia, adhere to reasonable construction. I am not a strict constructionist as I believe that would, on too frequent occasion, lead to the absurd outcomes about which Blackstone warned us and for which he provided a commonsense remedy.

Let me reiterate my view on where ultimate supremacy lies; it lies in the words, clauses, articles and whole document of the Constitution. There is long standing jurisprudential methodology that allows for faithful interpretation of those written words. Blackstone pointed the way in his Commentaries on the English Law and Chief Justice Marshall incorporated much of Blackstone’s methods into American jurisprudence. Blackstone and Marshall have constructed, not a mindless textual mantra, but a well-structured, rule-managed, accommodating, and flexible analytical process.

Interpretation of the Constitution’s words is further made possible by the nature of the constitutional compact. Court interpretation and application of constitutional meaning does not (or at least should not), on the vast majority of occasions direct the normal ongoing course of minor political affairs such as how we shall arrange traffic laws for an automobile society. Nor does it tell us how to arrange the work-a-day activities of the modern technological society nor does it create, erase, or enforce specific cultural norms. The Constitution and the power of constitutional interpretation is to be reserved to: 1) Maintain the overarching political relationships of the three branches of the federal government; 2) Maintain the power relationship between states and the national government and; 3) Defend the individual from denial of a restricted number of fundamental and sacred rights belonging in common to all.

There is much discussion today about the need for a so-called Living Constitution driven by judicial supremacy. The premise is that the Constitution must be capable of responding to the complex fast-changing problems of the twenty-first century. That Living Constitution has been present from the beginning and it is found in Articles I and II. The Congress and the President have always performed the functions of a “living constitution”. The duty to fashion new laws that address the problems of modernity falls to the Senate and to the House. There are committees for studying, analyzing, and addressing every modern problem. Each of those committees has access to the best and brightest experts in the world on every possible technological, social, and financial area of inquiry. It seems to me that the progressive postmodern Court has claimed to have found an authority to will social, cultural, and economic transformation simply because they want to.

I believe that the American republic is confronting several existential crises, one of which is a Court that has drifted rather far from the political agreements it made with the people, the states, and the other branches of government at the Founding. I believe that the Court’s duty and oath require it and me to exercise a good-faith allegiance to the original constitutional agreement. Postmodern Leftists have marched onto the American scene, destroyed constitutional America, and replaced it with central authoritarian rule by a self-anointed elite.

[1] The Dred Scott decision is excepted as a radical departure Constitution based interpretation. It brought such draconian impact and so clearly contradicted the from Constitution and its sister document the Declaration of Independence as to stand alone and apart from regular constitutional jurisprudence.

[2] Antonin Scalia, A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law, p. 29

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid, p. 38